Tracing the Roots of a Tradition

Photographing a Maracatu group with over 100 years of history

One of the things I’ve come to appreciate about Brazil is how much Brazilians love to share their culture. They don’t guard it. If you show interest, they welcome you in.

During this Carnival, my goal was clear: photograph Maracatu.

We left Olinda before the madness took over. I had been warned—it wouldn’t be what I was looking for. Not there. Not during Carnival. In Olinda, it would be about the blocos—open to everyone, a flood of people spilling into the streets, costumes, music, dancing, drinking. A celebration, yes. But not the kind I wanted to capture.

I was looking for something deeper.

Another thing I had been warned about: once Carnival started, getting in and out of Olinda would be nearly impossible because of the traffic and the flow of people.

So we left while we still could.

We headed inland, into the rural heart of Pernambuco, where the celebrations were smaller, less crowded—but in many ways, just as passionate. Maybe even more so.

There's one important detail: I’d mentioned the legendary old-school photographer in Recife—the man who first pointed me toward Maracatu. His name is Xirumba.

By pure chance, I encountered him again in a well-known corner restaurant, a familiar haunt where locals linger and conversations stretch into the afternoon.

I greeted him warmly, thanked him, and half-jokingly said it was his fault I was back here again. He smiled, and during our brief chat, he expressed genuine excitement at seeing me return to capture Carnival. Then he offered a tip: “You should be looking for the real Maracatu. The most interesting photos aren’t in the cities—they’re out in the countryside.” That’s when he mentioned Cambinda Brasileira.

Founded in 1918, Cambinda Brasileira is the oldest continuously running Maracatu Rural group in Brazil.

While Maracatu Nação—the regal, processional form—took root in Pernambuco’s urban centers, Maracatu Rural (also known as Maracatu de Baque Solto) was born in the sugarcane plantations of the Zona da Mata. It’s the Maracatu of the laborers, the working class, the outcasts—raw, unrefined, and pulsating with Afro-Indigenous rhythms and improvisation.

Unlike the slow, ceremonial pace of Maracatu Nação, such as during the Night of the Silent Drums, Maracatu Rural is wild, theatrical, unpredictable—explosive even. The Caboclos de Lança, the Lanced Warriors, are its most iconic figures: towering headdresses, heavy embroidered tunics, and spears wrapped in colorful ribbons. Their relentless movements—spinning, flipping, charging through the crowd—create a blur of color and motion.

And Cambinda Brasileira? They’ve carried this tradition for over a century. That’s exactly where I was headed.

I had already made a contact in Nazaré da Mata, a director of culture there. I immediately messaged her:

"Do you know if there’s any Maracatu happening at Cambinda Brasileira during carnival?"

She replied, "Nothing until Saturday."

Then, she gave me the number of a mestre—the leader of the group.

I got in touch.

Soon enough, I was on my way to Cambinda Brasileira, deep in the countryside, surrounded by sugarcane plantations just outside Nazaré da Mata.

We arrived late in the evening and stayed the night.

In the morning, I met the three brothers—the owners of Cambinda Brasileira. Lovely guys. Incredibly photogenic.

They’re in their seventies now, but they’re still deeply passionate about Maracatu. Their father had started the group, and they had taken on the responsibility of keeping it alive.

One of them casually mentioned that he had performed as a Caboclo de Lança just last year.

For context—the Caboclo de Lança outfit and gear weigh about 35 kilos. And you have to move, spin, and dance in it!

The brothers started setting up decorations. It seemed important to them that everything looked right. I’d heard that they want to preserve Maracatu as close as possible to the original form.

But, at first, the place was pretty still, almost too still.

Would this be what I had imagined? Or would it feel like some watered-down version of Maracatu?

Then, the quiet broke.

The performers arrived first. Then the crowd. Then more performers. And suddenly, the energy shifted.

Faces emerged, characters took shape—each one a potential photograph. The real magic of events like this isn’t just the performance; it’s the sheer concentration of people. A gathering where moments unfold unpredictably, where stories appear in an instant, where life plays out in countless ways—all waiting to be captured.

This was exactly what I had come for.

The before.

The quiet moments backstage. The lead-up to the performance.

Performers tightening laces, adjusting headdresses, brushing off dust, exchanging glances before the chaos.

I don’t know why, but I’ve always been drawn to what happens behind the performance—often more than the performance itself. How is the magic created? That’s what I’ve always wanted to see.

This was my chance. And unlike the busy, visually cluttered streets of Olinda, here I had something else—adobe houses, open space, the deep green of the sugarcane fields stretching into the distance.

A Maracatu Rural performance is a living spectacle, built around distinct characters, each with a role in the unfolding drama.

At the head of the procession are the King and Queen, ceremonial figures chosen from respected members of the community. Their presence is more symbolic than authoritative, a nod to the royal traditions woven into Maracatu’s history.

The Baianas move gracefully in their flowing, layered dresses, embodying the deep fusion of African, Indigenous, and Portuguese influences.

Their skirts swirl as they dance, adding rhythm to the visual chaos.

Among them are the Caboclos de Pena, adorned with towering peacock-feathered headdresses, moving in hypnotic unison with the beat of the drums.

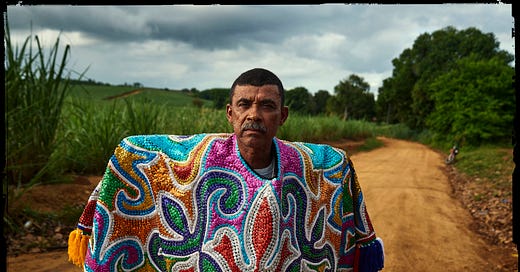

Then, there are the Caboclos de Lança—the warriors. Dressed in shimmering capes and heavy embroidered tunics, they wield wooden spears wrapped in ribbons, their movements aggressive, their presence commanding. They are the pulse of Maracatu Rural, the force that drives the energy forward.

Around them, the Umbrella Bearers add yet another layer of movement, twirling their bright, multicolored umbrellas, spinning like bursts of color amid the chaos.

I stayed on the edges once the performance began. Too many people, too many photographers.

I didn’t want my shots filled with cameras and tripods—I wanted to document Maracatu itself, its characters, its essence. Not clusters of people staring into their viewfinders and screens.

Maybe that was a little idealistic, but that was my challenge. That’s what I was after.

I kept searching for those small, unscripted moments. The interactions, the fleeting glances, the way people moved when they weren’t performing for an audience.

For all the extroversion of Brazilians, there’s one thing that can drive a photographer crazy.

The moment people see a camera pointed at them, nine times out of ten, they flash a wide grin and throw up a thumbs-up. A reflex. An instinct.

So I worked around it. Stayed discreet. Caught people before they noticed me. Or, when I had to, I’d simply ask—"Can you please not do that? Be natural."

Suddenly, the Caboclos de Lança—the warriors—gathered, then burst into a run, spears in hand, bells clanging in chaotic rhythm.

They surged forward along the dirt road, cutting through the sugarcane fields.

This—this was the image I had envisioned before I even arrived. The rawness, the movement, the energy of Maracatu Rural spilling into the landscape.

I sprinted ahead, camera in hand, positioning myself before they closed the distance. A few quick exposures—capturing the rush, the blur of sequins, the spears slicing through the air, streaks of color against the green.

The atmosphere was electric. Drums pounded. Bells rang in sharp, metallic bursts. The warriors moved as one, a living pulse of energy and tradition. People on the sidelines held their breath, wide-eyed, caught in the moment. The past and present colliding in sound, movement, and ritual.

And then, it was over.

What I had witnessed was only the beginning—a ritual before the Maracatu group set off for days of performances across different towns.

The truck carrying the performers' heavy costumes and gear pulled up, its doors swinging open. One by one, they lined up, loading their elaborate outfits inside, the energy of the day fading into the quiet work of packing up.

A few meters away, a bus idled, waiting to transport them to their next destination. Another striking scene—twilight settling over the sugarcane fields, a bus surrounded by people in the middle of it all, the last remnants of movement before the night swallowed everything. I kept shooting until the last person was gone.

But I didn’t follow.

I wanted to conserve my energy for what lay ahead—to search for more of these rural Maracatus, rather than chasing the same crowds and competing with other photographers in the bigger towns. So we stayed another night.

The place that had been alive with music and movement was silent now. Only the distant echoes of music from nearby Nazaré da Mata carried through the night.

The next morning felt surreal. The energy, the people, the spectacle—it was all gone. It was hard to imagine it had ever been here. Only scattered ribbons stretched between poles and bits of rubbish left behind hinted at what had taken place.

Hi Mittchell!

I follow you for years now and I am very glad you are around here to see Carnaval and the Maracatu. I am also an enthuisiast photographer of the Maracatu. I live in the south of Brazil and of course have a series of photos taken of the Maracatú Noval Lua (in Santa Catarina) and this year I went to Belo Horizonte to check the Baque de Mina. I was quite an experience.

Congratulations for your photos - they really got that antecipation feeling tha goes on before the presentations. AXÉ!

Hello, Mitchell:

This is a spectacular series! And your narrative complements the photography perfectly.

We have one thing in common, the desire to see “backstage” when performers become regular people again. My first experience was at a fashion show. I slipped backstage and found the models smoking, drinking soda or touching up their makeup. Some, exhausted, just relaxed waiting for the next call.

I cannot help but imagine some future date when, sitting in a darkened theater, I see the screen light up with the words, “A film by Mitchell Kanashkevich”.